(Mains GS 2 : Issues relating to development and management of Social Sector/Services relating to Health, Education, Human Resources.)

Context:

- In November 2021, Department of Expenditure, the Ministry of Finance released ₹8,453.92 crore to 19 States as a health grant to rural and urban local bodies (ULBs).

- The grants have been released as per the recommendations of the Fifteenth Finance Commission.

Plugging the gaps:

- The commission, in its report for the period from 2021-22 to 2025-26, had recommended a total grant of ₹4,27,911 crore to local governments.

- The grants recommended by the commission inter alia include health grants of ₹70,051 crore.

- Of this ₹70,051 crore amount, ₹43,928 crore has been recommended for rural local bodies and ₹26,123 crore for urban local bodies.

- These grants are meant to strengthen healthcare systems and plug critical gaps at the primary healthcare level in rural and urban settings.

Identified interventions:

- The finance commission has identified interventions that will directly lead to strengthening the primary health infrastructure and facilities in both rural and urban areas and earmarked grants for each intervention.

- These interventions include support for diagnostic infrastructure to the primary healthcare facilities in rural areas (₹16,377 crore), block-level public health units in rural areas (₹5,279 crore), construction of buildings at sub centres, PHCs, CHCs in rural areas (₹7,167 crore), among others.

- Strengthening the local governments in terms of resources, health infrastructure and capacity building can enable them to play a catalytic role in epidemics and pandemics too.

Significant grant:

- The grant is equal to 18.5% of the budget allocation of the Union Department of Health and Family Welfare for FY 2021-22 and around 55% of the second COVID-19 emergency response package announced in July 2021.

- However, it is arguably the single most significant health allocation in this financial year with the potential to have a far greater impact on health services in India in the years ahead.

- Both urban and rural India need more health services; however, the challenge in rural areas is the poor functioning of available primary health-care facilities while in urban areas, it is the shortage of primary health-care infrastructure and services both.

Deliver primary care:

- In 1992, as part of the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments, the local bodies (LBs) in the rural (Panchayati raj institutions) and urban (corporations and councils) areas were transferred the responsibility to deliver primary care and public health services.

- The hope was this would result in greater attention to and the allocation of funds for health services in the geographical jurisdiction of the local bodies.

Lack of clarity on responsibilities:

- The rural settings continued to receive funding for primary health-care facilities under the ongoing national programmes but government funding for urban primary health services was not channelled through the State Health Department.

- The ULBs (which fall under different departments/systems in various States) did not make a commensurate increase in allocation for health.

- The reasons included a resource crunch or a lack of clarity on responsibilities related to health services or completely different spending priorities.

Less health care spending:

- In 2005, the launch of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) to bolster the primary health-care system in India partly ameliorated the impact of RLBs not spending on health.

- However, urban residents were not equally fortunate as the National Urban Health Mission (NUHM) could be launched eight years later and with a meagre annual financial allocation which never crossed ₹1,000 crore.

- In 2017-18, 25 years after the Constitutional Amendments, the ULBs and RLBs in India were contributing 1.3% and 1% of the annual total health expenditure in India.

Some challenges:

- Urban India, with just half of the rural population, has just a sixth of primary health centres in comparison to rural areas.

- The low priority given to and the insufficient funding for health is further compounded by the lack of coordination between a multitude of agencies which are responsible for different types of health services.

- Regular outbreaks of dengue and chikungunya and the struggle people have had to undergo to seek COVID-19 consultation and testing services in two waves of the novel coronavirus pandemic are some examples.

Way forward:

- The Fifteenth Finance Commission health grant is an unprecedented opportunity to fulfil the mandate provided under the two Constitutional Amendments, in 1992.

- Thus, the grant should be used as an opportunity to sensitise key stakeholders in local bodies, including the elected representatives and the administrators, on the role and responsibilities in the delivery of primary care and public health services.

- Further, awareness of citizens about the responsibilities of local bodies in health-care services should be raised. Such an approach can work as an empowering tool to enable accountability in the system.

More steps to acknowledge:

- The civil society organisations need to play a greater role in raising awareness about the role of LBs in health, and possibly in developing local dashboards (as an mechanism of accountability) to track the progress made in health initiatives.

- The Fifteenth Finance Commission health grants should not be treated as a ‘replacement’ for health spending by the local bodies, which should alongside increase their own health spending regularly to make a meaningful impact.

- Mechanisms for better coordination among multiple agencies working in rural and urban areas should be institutionalised. Time-bound and coordinated action plans with measurable indicators and road maps need to be developed.

- The young administrators in charge of such RLBs and ULBs and the motivated councillors and Panchayati raj institution members need to grab this opportunity to develop innovative health models.

- Further, before the novel coronavirus pandemic started, a number of State governments and cities had planned to open various types of community clinics in rural and urban areas. But this was derailed. The funding should be used to revive all these proposals.

Conclusion:

- Rural and urban local bodies can play a key role in the delivery of primary healthcare services, especially at the ‘cutting-edge’ level and help in achieving the objective of universal healthcare.

- Thus, the Fifteenth Finance Commission health grant has the potential to create a health ecosystem which can serve as a much-awaited springboard to mainstream health in the work of rural and urban local bodies.

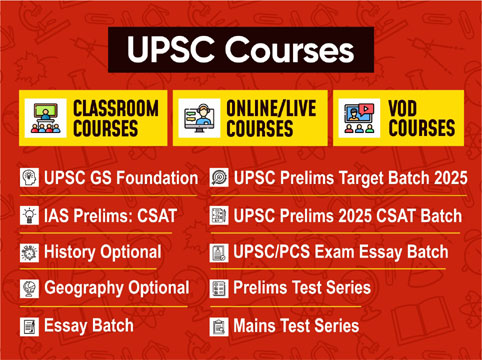

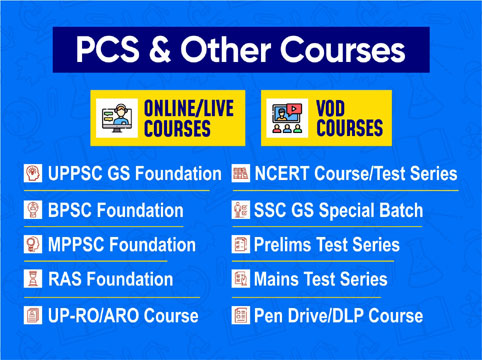

Contact Us

Contact Us  New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757

New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757  Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757

Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757