(MainsGS2:Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.)

Context:

- The Ministry of Electronics and IT has been actively organising consultations on the proposed “Digital India Bill” to build conceptual alignment on a new law that will replace India’s 23-year-old Information Technology (IT) Act.

Tackle emerging challenges:

- The goal is to upgrade the current legal regime to tackle emerging challenges such as user harm, competition and misinformation in the digital space.

- And this is a much-anticipated piece of legislation that is likely to redefine the contours of how technology is regulated, not just in India but also globally.

- Changes being proposed include a categorisation of digital intermediaries into distinct classes such as e-commerce players, social media companies, and search engines to place different responsibilities and liabilities on each kind.

Current regime:

- The current IT Act defines an “intermediary” to include any entity between a user and the Internet, and the IT Rules sub-classify intermediaries into three main categories: “Social Media Intermediaries” (SMIs), “Significant Social Media Intermediaries” (SSMIs) and the recently notified, “Online Gaming Intermediaries”.

- SMIs are platforms that facilitate communication and sharing of information between users, and SMIs that have a very large user base (above a specified threshold) are designated as SSMIs.

- However, the definition of SMIs is so broad that it can encompass a variety of services such as video communications, matrimonial websites, email and even online comment sections on websites.

- The rules also lay down stringent obligations for most intermediaries, such as a 72-hour timeline for responding to law enforcement asks and resolving ‘content take down’ requests.

- Unfortunately, ISPs, websites, e-commerce platforms, and cloud services are all treated similarly.

Global position:

- Only a handful of countries have taken a clear position on the issue of proportionate regulation of intermediaries, so there is not too much to lean on.

- The European Union’s Digital Services Act is probably one of the most developed frameworks for us to consider.

- It introduces some exemptions and creates three tiers of intermediaries — hosting services, online platforms and “very large online platforms”, with increasing legal obligations.

- Australia has created an eight-fold classification system, with separate industry-drafted codes governing categories such as social media platforms and search engines.

- Intermediaries are required to conduct risk assessments, based on the potential for exposure to harmful content such as child sexual abuse material (CSAM) or terrorism.

Proportionate regulation:

- While a granular, product-specific classification could improve accountability and safety online, such an approach may not be future-proof.

- As technology evolves, the specific categories we define today may not work in the future.

- Therefore the need is to have a classification framework that creates a few defined categories, requires intermediaries to undertake risk assessments and uses that information to bucket them into relevant categories.

- As far as possible, the goal should also be to minimise obligations on intermediaries and ensure that regulatory asks are proportionate to ability and size.

Undertake risk assessments:

- Intermediaries that offer communication services could be asked to undertake risk assessments based on the number of their active users, risk of harm and potential for virality of harmful content.

- The largest communication services (platforms such as Twitter) could then be required to adhere to special obligations such as appointing India-based officers and setting up in-house grievance appellate mechanisms with independent external stakeholders to increase confidence in the grievance process.

- Alternative approaches to curbing virality, such as circuit breakers to slow down content, could also be considered.

Conclusion:

- For the proposed approach to be effective, metrics for risk assessment and appropriate thresholds would have to be defined and reviewed on a periodic basis in consultation with industry.

- Overall, such a framework could help establish accountability and online safety, while reducing legal obligations for a large number of intermediaries.

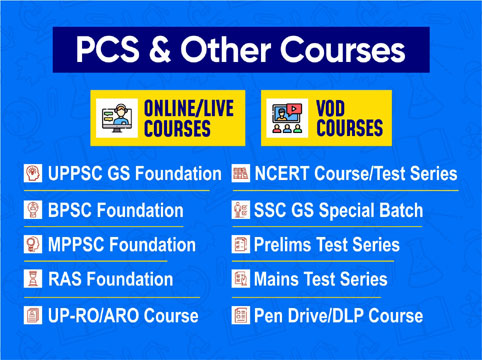

Contact Us

Contact Us  New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757

New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757  Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757

Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757