(GS-3: Issues related to direct and indirect farm subsidies and minimum support prices Public Distribution System-objectives, functioning, limitations.)

Context:

- The Economic Survey rightly flagged the issue of a growing food subsidy bill, which “is becoming unmanageably large”.

- The reason is not far to seek. Food subsidy, coupled with the drawal of food grains by States from the central pool under various schemes, has been on a perpetual growth trajectory.

Increasing food subsidies:

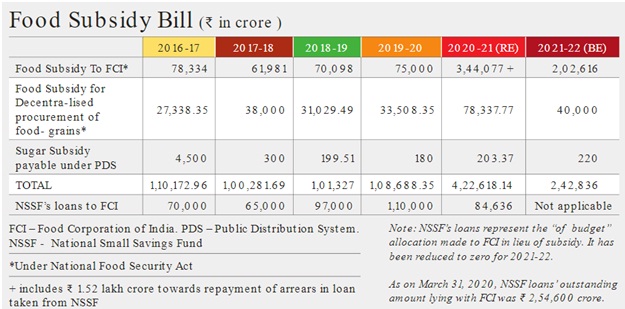

- During 2016-17 to 2019-20, the subsidy amount, clubbed with loans taken by the Food Corporation of India (FCI) under the National Small Savings Fund (NSSF) towards food subsidy, was in the range of ₹65-lakh crore to ₹2.2-lakh crore.

- In future, the annual subsidy bill of the Centre is expected to be about ₹5-lakh crore.

- For this financial year (2020-21) which is an extraordinary year on account of the COVID-19 pandemic, the revised estimate of the subsidy has been put at about ₹23-lakh crore, excluding the extra budgetary resource allocation of ₹84,636 crore.

High withdrawal rate:

- During the three years, the quantity of food grains drawn by States (annually) hovered around 60 million tonnes to 66 million tonnes.

- Compared to the allocation, the rate of drawal was 91% to 95%.

- As the National Food Security Act (NFSA), which came into force in July 2013, enhanced entitlements (covering two-thirds of the country’s population), this naturally pushed up the States’ drawal.

- Based on an improved version of the targeted Public Distribution System (PDS), the law requires the authorities to provide to each beneficiary 5 kg of rice or wheat per month.

- Till December 2020, the Centre set apart 94.35 million tonnes to the States under different schemes including the NFSA and additional allocation, meant for distribution among the poor free of cost.

Issue price and politics:

- Economic Survey has hinted at an increase in the Central Issue Price (CIP).

- This has remained at ₹2 per kg for wheat and ₹3 per kg for rice for years, though the NFSA.

- What makes the subject more complex is the variation in the retail issue prices of rice and wheat.

- From nil in States such as Karnataka and West Bengal for Priority Households (PHH) and Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) ration card holders, ₹1 in Odisha for both categories of beneficiaries to ₹3 and ₹2 in Bihar for the two categories.

- In Tamil Nadu, rice is given free of cost for all categories including non-PHH.

Political will required:

- It is difficult to reduce “the economic cost of food management in view of rising commitment” by the political parties, towards food security.

- Central government does not want the NFSA norms to be disturbed.

- But, a mere increase in the CIPs of rice and wheat without a corresponding rise in the issue prices by the State governments would only increase the burden of States, which are already under the problem of a resource crunch.

- Political compulsions are perceived to be coming in the way of the Centre and the States increasing the prices.

- Thus keeping so low the retail prices of food grains at fair price shops, even after the passage of nearly 50 years and achieving substantial poverty reduction in the country is now not rationale.

- As per the Rangarajan group’s estimate in 2014, the share of people living below the poverty line (BPL) in the 2011 population was 29.5% (about 36 crore).

Suggested Reforms:

- It is time the Centre had a relook at the overall food subsidy system including the pricing mechanism.

- It should revisit NFSA norms and coverage.

- An official committee in January 2015 called for decreasing the quantum of coverage under the law, from the present 67% to around 40%.

- For all ration cardholders drawing food grains, a “give-up” option, as done in the case of cooking gas cylinders, can be made available.

- Even though States have been allowed to frame criteria for the identification of PHH cardholders, the Centre can nudge them into pruning the number of such beneficiaries.

- As for the prices, the existing arrangement of flat rates should be replaced with a slab system.

- Barring the needy, other beneficiaries can be made to pay a little more for a higher quantum of food grains.

- The rates at which these beneficiaries have to be charged can be arrived at by the Centre and the States through consultations.

- Computerization of operations, digitisation of data of ration cardholders, seeding of Aadhaar, and automation of fair price shops will be ensured.

- These measures, if properly implemented, can have a salutary effect on retail prices in the open market.

Conclusion:

- Yet, diversion of food grains and other chronic problems do exist.

- It is nobody’s case that the PDS should be dismantled or in-kind provision of food subsidy be discontinued.

- After all, the Centre itself did not see any great virtue in the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) mode at the time of giving additional food grains free of cost to the States during April-November last year (as part of relief measures during the pandemic).

- Thus, a revamped, need-based PDS is required not just for cutting down the subsidy bill but also for reducing the scope for leakages.