(MainsGS2: Functions and responsibilities of the Union and the States, issues and challenges pertaining to the federal structure, devolution of powers and finances up to local levels and challenges therein.)

Context:

- Signs of a confrontation between Raj Bhavan and the elected government in a State are not infrequent in the country.

- The Governors are once again becoming public spectacles in many States, as seen in Punjab, Maharashtra, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Delhi, and in a few others earlier.

Populist posturing:

- While there have been endless arguments on whether the Governor enjoys discretionary authority or not and if he does, under what constitutional and legal provisions , they may not be able to clinch the argument on an issue as they do not necessarily rule out the contrarian stances.

- One of the examples of populist posturing is to play the blame game and accuse the other party of doing the same when it was in power.

- While such charges may be factually correct or close to the charge, bad precedents may not be good examples to imitate.

- These charges also do not take into account the great churning that the Indian polity has undergone over the years and the challenges that institutions confront to remain abreast with them.

Greater devolution of responsibilities:

- The arena of the relative autonomy of States underwent a decisive turn from the late 1980s without formally altering the constitutional frame very much.

- This transformation was manifest in the rise of new political parties with their focus on States, liberalisation of the economy, and greater devolution of economic responsibility to the States.

- This shift of power and responsibility was also reflected in policy measures such as the 73rd and 74th Amendments to the Constitution authorising local governance, inclusion and devolution of powers; reforms initiated by P.V. Narasimha Rao-Manmohan Singh team on the economy; and judicial verdicts such as the Bommai case that mandated that the invocation of President’s rule in States called for wider political consensus.

Complementary role:

- The relative autonomy of States has enhanced their presence as well as responsibilities.

- This enhanced role of the States does not in any way challenge Union powers, but generally tends to complement and supplement the new challenges and opportunities that it faces.

- The fears of centripetal tendencies that marked the early years of Independence no more hold good as far as the broad expanses of India are concerned.

- Strong States were not seen as an affront to national unity but the latter itself was conceptualised as being forged through robust regional bonds.

Following public voices:

- While the constitutional reasoning that resulted in the institution of Governor in India may still hold good today, it calls for a re-orientation.

- As the constitutional head of the State, there are innumerable concerns, particularly the Directive Principles of State policy, that could be the frame of conversation of the Governor with his government.

- Such a conversation, however, needs to be in the form of an engagement with his government and the State legislature rather than meant to project him as an independent power centre.

- The changed context also calls for listening to and closely following public voices and deliberated reasoning in the State and elsewhere rather than harping on constitutional status.

Conclusion:

- As a link between State and the Centre, a Governor brings the wider concerns and promises of the State to the attention of the Centre as well as the public at large, which partisan politics may tend to sidestep.

Contact Us

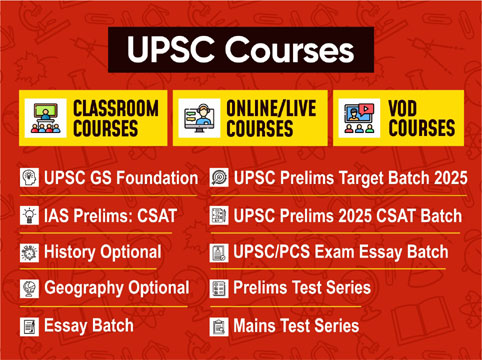

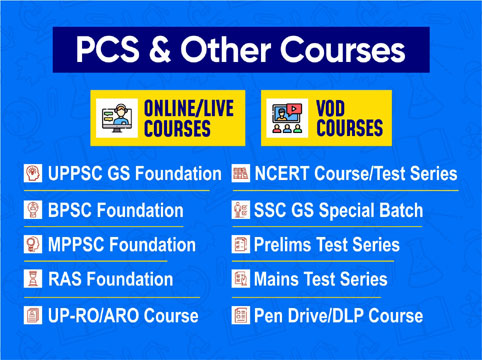

Contact Us  New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757

New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757  Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757

Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757