(Prelims: Current events of national and international importance, general issues related to environmental ecology, biodiversity, and climate change)

(Mains, General Studies Paper 3: Conservation, Environmental Pollution and Degradation, Environmental Impact Assessment)

Context

On September 17, 2025, the European Union (EU) and India set out a new comprehensive strategic agenda in their joint communication. Called the "New Strategic EU-India Agenda," it is a blueprint for strengthening the partnership between the two countries.

Key Points

- It discusses five key pillars (agenda) around which their partnership will be enhanced.

- These five key pillars focus on five areas: prosperity and sustainability, technology and innovation, security and defense, connectivity and global issues, and cross-pillar enablers (support mechanisms).

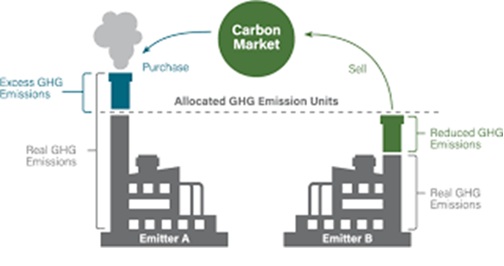

- A key announcement in the Clean Energy Transition section of this agenda is that the Indian Carbon Market (ICM) will be linked to the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

- This simply means that the carbon price paid in India will be deducted from the CBAM fee at the EU border, avoiding double penalties for Indian exporters and encouraging earlier decarbonization.

- This is a historic step in North-South carbon market cooperation that aligns global climate goals with trade. However, practical hurdles remain.

Immaturity of the Indian Carbon Market: Key Challenges

- Current Status of the ICM: India's Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS), also known as the ICM, is still in its development stage. It is less developed than the EU's Emissions Trading System (ETS), which has two decades of experience in its auction structure, cap-setting process, and independent verification.

- Differences in the nature of credits: Currently, ICM reforms are based on intensity or project-based offsets, rather than absolute limits on emissions, which ICM is moving towards. CBAM requires strict calculation of the carbon embedded in commodities, tonne-by-tonne.

- Institutional weaknesses: India lacks an independent regulator or emissions registry like the EU, raising questions about market integrity and causing the EU to view Indian credits as second-rate.

- Need for structural restructuring: ICM needs to be strengthened with a legally binding cap and penalty system similar to the EU ETS, which requires major changes to bureaucracy and operations.

- Consequences: Without these reforms, the EU will be hesitant to decouple the Indian carbon price from CBAM, which could hinder integration.

Price Differences and Political Risks: Practical Obstacles

- Large carbon price differential: The EU ETS price is €60-80 per tonne, while the initial credit in India ranges from €5-10, making CBAM reductions ineffective.

- Fear of double burden: Exporters may be forced to pay the full EU CBAM fee in addition to compliance costs in India, leading to pressure from industry lobbies to weaken ICM compliance standards.

- Solution options: Sector-specific carbon contracts or negotiations on a minimum price in line with CBAM are possible, but these are politically complex and may conflict with the interests of domestic industries.

- Political implications: This risk will spark political debate in India, with industries opposing “double payments” and demanding a weakening of ICM.

- Linkages: Bridging the price gap requires not only technical but also political compromises, which can strengthen or weaken cooperation.

The Fundamental Nature of CBAM: Controversial Dimensions

- Opposition from Developing Countries: Developing nations, including India, view CBAM as a unilateral and protectionist measure at the WTO and international forums. Its linkage would question the legitimacy of India's prior resistance.

- Political Contradictions: Accepting the linkage would legitimize CBAM, creating controversy in domestic politics. If the EU deems the Indian price "inadequate," exporters will complain, and India will have to fight it legally or politically.

- Sovereignty Issue: Carbon assessment is a domestic policy, but CBAM gives the EU the right to examine the "adequacy" of India's measures, which could be a red line for a sovereignty-protective country like India.

- Strategic Risk: The linkage depends on WTO laws as well as domestic political economy and EU-India trust. Any domestic backsliding (such as reducing compliance due to industry pressure) could destabilize exports.

- Relationship: The contentious nature of CBAM hinders cooperation, but if resolved, it could become a global model.

Optimistic Solution: Avenues for Cooperation

- Potential for Comprehensive Cooperation: The ICM-CBAM linkage is one of the most important agreements between global economies. If successful, it will protect Indian exporters, accelerate industrial decarbonization, and become a model for North-South cooperation.

- India's Role: Strengthening market design, such as adopting a full cap-and-trade system, will increase transparency with the EU.

- EU role: Provide clarity, technical assistance and simplified rules for small businesses (e.g. relief for small exporters in CBAM) to ensure a smooth transition

- Long-term benefits: This linkage could make India a global carbon finance hub by linking climate goals with trade, but without reforms, it will remain on paper.

- Relationship: Optimistically, joint efforts on both sides can turn obstacles into opportunities, promoting global stability.

The Way Forward

The EU-India agenda is the beginning of carbon market cooperation, based on environmental integrity, trade fairness, and political trust, which has obstacles but solutions are possible. India needs to strengthen the ICM, ensure price parity, and enhance dialogue at the WTO level, while the EU should provide support.