“Water is life – and if society is aware, water is secure.”

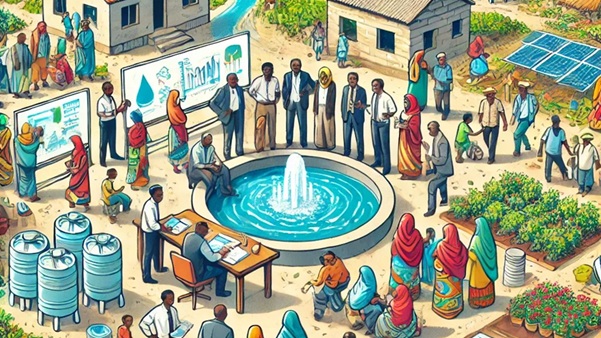

In India, the water crisis has become a matter of national concern. Rapid population growth, urbanization, industrialization, and climate change have placed immense pressure on water resources. In such a scenario, government schemes alone are not sufficient—active participation of local communities is the key to sustainable solutions.

Status of Water Crisis in India

|

Indicator

|

Status

|

|

Per capita water availability (1951)

|

5177 cubic meters/year

|

|

Per capita water availability (2025)

|

1400 cubic meters/year

|

|

India’s share of global population

|

18%

|

|

India’s share of global water resources

|

Only 4%

|

|

Groundwater extraction

|

Highest in the world (25%)

|

- According to the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), more than 700 blocks are categorized as “critical or over-exploited.” India is in a state of water stress.

Why Community-Based Water Conservation is Essential

- Local Knowledge and Traditions

- Rural India has long practiced rainwater harvesting and used community-based systems like ponds, stepwells, johads, and ahar-pyne.

- Sense of Ownership

- When people themselves are part of the planning and execution, they feel responsible for protecting and maintaining water sources.

- Decentralized Water Management

- Local decision-making ensures that plans suit the region’s geography, culture, and needs.

- Limitations of Top-Down Government Programs

- Centralized approaches often fail at the grassroots level without community consent and involvement.

Major Models of Community Participation

- Johad Model (Rajasthan) – Rajendra Singh (Waterman of India)

- Revived water bodies in Alwar district through community-built johads.

- Rivers like Arvari and Ruparel began flowing again—an exemplary model of “people-led water revival.”

- Pani Panchayat Model (Maharashtra)

- Initiated in the 1980s based on principles of equitable water distribution and collective decision-making.

- Farmer groups ensured social equity in irrigation and water use.

- Sardar Patel Participatory Water Conservation Program (Gujarat)

- Partnership among farmers, NGOs, and government for building check dams.

- Resulted in significant groundwater recharge across thousands of villages.

- Chaal-Khaal and Naula Systems (Himalayan States)

- Communities in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh maintain and recharge traditional water sources through cleaning and reforestation.

- Kudimaramathu (Tamil Nadu)

- Ancient tradition where villagers voluntarily maintained tanks and ponds; now revived by the government.

Policy and Institutional Initiatives

|

Policy / Scheme

|

Community Provisions

|

|

Jal Shakti Abhiyan (2019)

|

Promotes “Jan Andolan to Jan Bhagidari” – public participation; Catch the Rain campaign.

|

|

Atal Bhujal Yojana

|

Community-based groundwater management involving Panchayats in planning, execution, and monitoring.

|

|

MGNREGA

|

Construction of ponds, check dams, and water harvesting structures through collective labor and participation.

|

|

Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM)

|

Provides piped water to every rural household; operated by village water committees.

|

|

National Water Policy (Draft 2023)

|

Emphasizes revival of community and traditional water management systems.

|

Benefits of Community-Based Water Conservation

- Sustainable Use of Resources – Collective control curbs overexploitation.

- Environmental Regeneration – Recharge of water sources enhances biodiversity and soil productivity.

- Social Cohesion and Empowerment – Strengthens local institutions like Panchayats, women’s groups, and farmer collectives.

- Economic Gains – Better water availability boosts agricultural productivity and rural incomes.

- Climate Adaptation – Enhances resilience to droughts through rainwater harvesting and local preparedness.

Key Challenges

|

Problem

|

Description

|

|

Social Inequality

|

Dominance of powerful groups limits participation of marginalized communities.

|

|

Lack of Technical Knowledge

|

Inadequate integration of traditional wisdom with modern technology.

|

|

Financial Sustainability

|

Many projects start but fail to sustain due to poor maintenance funding.

|

|

Irregular Government Support

|

Lack of policy continuity and coordination.

|

|

Limited Urban Participation

|

Citizen engagement in urban water conservation remains low.

|

Way Forward

- Expand Water Panchayats and Water User Associations—recognize local decision-making.

- Ensure women’s participation—they are key stakeholders in water management.

- Integrate technology with traditional wisdom—GIS, sensors, and rainwater harvesting with indigenous methods.

- Strengthen education and awareness—promote water literacy from school level.

- Introduce performance-based incentives—reward villages achieving water conservation goals.

- Promote urban citizen-led initiatives—mandatory greywater recycling and rainwater systems in housing societies.

- Encourage river rejuvenation projects—community monitoring committees for river health (e.g., Ganga rejuvenation).

Conclusion

- “Water conservation is possible not by governments alone, but through collective action by society.” In India’s ancient philosophy, water was revered as sacred—seen as Nadi Devata or Talab Devata. Today, this reverence must be revived through modern policy and community synergy.

- Community-based water management = Local Knowledge + Social Cooperation + Scientific Policy

- If every village, ward, and city takes ownership of water conservation, India can truly become a Water-Secure Nation by 2047.