(MinsGS3: Conservation, environmental pollution and degradation, environmental impact assessment.)

Context:

- Recently, the Supreme Court asked the Government, whether a focussed approach, something like Project Tiger, can be taken up for saving the critically endangered Great Indian Bustard (GIB).

Court’s direction:

- Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud directed Chief Secretaries of Gujarat and Rajasthan to undertake and complete a comprehensive exercise within four weeks to find out the total length of transmission lines in question and the number of bird diverters required.

- Earlier, in April 2021, the Supreme Court had directed the authorities to convert the overhead cables into underground power lines, (where feasible) within a period of one year and that till such time diverters would have to be hung from existing power lines.

Threat due to power lines:

- There are several threats that have led to the decline of the GIB populations; however, power lines seem to be the most significant.

- Like other species of bustards, the GIBs are large birds standing about one metre tall and weighing about 15 to 18 kgs.

- The GIBs are not great fliers and have wide sideways vision to maximise predator detection but the species’ frontal vision is narrow.

- These birds cannot detect power lines from far and since they are heavy fliers, they fail to manoeuvre across power lines within close distances.

- The combination of these traits makes them vulnerable to collision with power lines where in most cases, death is due to collision rather than electrocution.

Steps taken:

- Listed in Schedule I of the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, in Appendix I of CITES, as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List, the GIBs enjoy the highest protection both in India and globally.

- Historically, the GIB population was distributed among 11 States in western India but today the population is confined mostly to Rajasthan and Gujarat and only a small populations are found in Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.

- Along with the attempts to mitigate impacts of power transmission lines on the GIB, steps have been taken for conservation breeding of the species.

- Chicks, artificially hatched from eggs collected from the wild, are being reared in the satellite conservation breeding facility at Sam in Jaisalmer, Rajasthan.

- The objective of ‘Habitat Improvement and Conservation Breeding of Great Indian Bustard-an integrated approach’ is to build the captive population of the GIBs and to release the chicks in the wild.

- Experts, including scientists from the WII, have called for removing all overhead power lines passing through the GIB priority/critical areas in Rajasthan; the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change too has constituted a task force.

Other threats:

- According to scientists, the GIBs are slow breeders and they build their nests on the ground thus being subjected to hunting and egg collection in the past.

- There also has been a decline in prevailing habitat loss as dry grasslands have been diverted for other use.

- Experts also warn of pesticide contamination and increase of populations of free-ranging dogs and pigs along with native predators (fox, mongoose, and cat), putting pressure on nests and chicks.

- While most of the population of the species is confined to the Jaisalmer Desert National Park (DNP), wildlife enthusiasts believe that more areas outside the protected area must be made suitable for the species.

Conclusion:

- A conservation effort like ‘Project Tiger’ may not work for a large bird of an arid region that can always fly out of the protected area. Experts are calling for community-centric conservation of the critically endangered species.

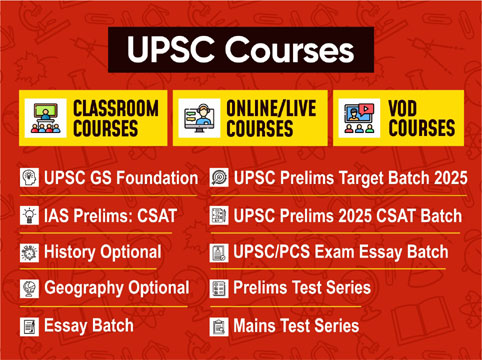

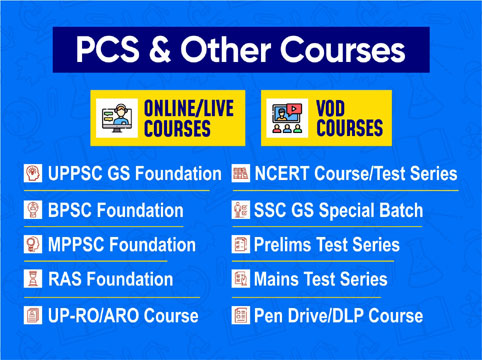

Contact Us

Contact Us  New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757

New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757  Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757

Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757